Programming the ODROID-GO: Build System (Part 1)

Before we can write any code for the ODROID-GO, we first need to get the ESP32’s SDK set up. It contains the code that actually gets the ESP32 to boot and call into our main function, as well as code for peripherals like SPI which we’ll need to use when we write our LCD driver.

Espressif calls the SDK the ESP-IDF and we’ll be using the latest stable version which is v4.0.

We can either clone the repository per their instructions (with the recursive flag) or just download the zip from the releases page.

Our first objective is to get a minimal Hello World sort of application deployed to our ODROID-GO that proves our build environment is properly configured.

C vs C++

The ESP-IDF uses C99 so that’s what we’ll use as well. We could use C++ if we wanted to (there is a C++ compiler in the ESP32 toolchain) but we’re going to stick with C for now.

I actually like C quite a bit and find its simplicity refreshing. No matter how much time I spend writing C++ code, I can never quite get to the point where I enjoy it. This person sums up my thoughts pretty well.

Besides, we can always switch to C++ in the future if needed.

Minimal Project

The IDF uses CMake to manage the build system. It also supports Makefiles but that is now deprecated as of v4.0, so we’ll just use CMake.

At the very minimum we need a CMakeLists.txt file describing our project, a main directory that contains a source file with the entry point into our game, and another CMakeLists.txt file inside of main that lists our source files.

CMake needs to reference some environment variables that tell it where to find the IDF and where to find the toolchain. I found it annoying to have to set them all again every time I started a new terminal session, so I wrote a script called export.sh to do the work for me. It sets IDF_PATH and IDF_TOOLS_PATH and sources the IDF export which sets up other environment variables.

All that’s needed of someone using the script is to set the IDF_PATH and IDF_TOOLS_PATH variables.

| |

The root CMakeLists.txt:

| |

By default the build system will build every possible component inside of $ESP_IDF/components which causes our compilation time to be longer than necessary. Instead we want the bare minimum set of components required to get our main function called, and then we can add additional components later as we require them. That’s what the COMPONENTS variable does.

We tell the IDF to look in the src directory for the code for our game with EXTRA_COMPONENT_DIRS and specifying src in COMPONENTS. The esptool_py component is required for flashing the binary to the ESP32.

The CMakeLists.txt inside of src:

| |

The main.c is as simple as it gets:

| |

All this does is print “Hello World” to the serial monitor every second forever. The vTaskDelay is using FreeRTOS to delay.

Notice that our function is called app_main and not main. The actual main function is used by the IDF to do necessary set up and then it creates a task with our function app_main as its entry point.

A task is just a unit of execution that FreeRTOS can schedule. We don’t really have to worry about it right now (or maybe ever) but the important thing to note is that our game is running on a single core (the ESP32 actually has two cores), and the task is delayed execution for one second with every iteration of the for loop. During that delay the FreeRTOS scheduler is free to go and execute other code that is waiting for its turn to run, if there is any.

We may opt to use both cores but for now we’ll just stick with a single core.

Components

Even if we reduce the list of components to the bare minimum required for a Hello World application (which is esptool_py), it still builds some other components that we don’t need due to the way the dependency chain is set up. It will build all of the following:

| |

A lot of those make sense (bootloader, esp32, freertos), but then there are those that we don’t need because we aren’t using any networking features: esp_eth, esp_wifi, lwip, mbedtls, tcpip_adapter, wpa_supplicant. Unfortunately we still have to build those components.

Thankfully the linker is smart enough to not link unused components into our final game binary. We can verify that with make size-components.

| |

The absolute biggest contributor to our binary’s size is libc and that’s okay.

Project Configuration

The IDF allows us to set compile-time configuration parameters that it uses during build to enable and disable different features. There are a few parameters that we should set that let us take advantage of some of the extras provided by the ODROID-GO.

First we need to source the export.sh script so that CMake has access to the necessary environment variables. Then, like all CMake projects, we need to create a build directory and call CMake from within it.

| |

If we run make menuconfig, we’ll get a window to configure project-specific settings.

Enabling Optimizations

We’ll enable optimizations to increase performance. Normally optimizations makes debugging code more difficult because they change the code flow, but we aren’t able to debug anyway because we don’t have access to JTAG.

We can enable them by going to Compiler options -> Optimization Level -> Release (-Os).

Expanding flash to 16MB

The ODROID-GO expands the default amount of flash storage to 16MB which we can enable by going to Serial flasher config -> Flash size -> 16MB.

Enabling external SPI RAM

We also have access to an additional 4MB of external RAM connected via SPI. We can enable it by going to Component config -> ESP32-specific -> Support for external, SPI-connected RAM and pressing Space to enable it. We would like to be able to explicitly allocate memory from the SPI RAM which we can enable by going to SPI RAM config -> SPI RAM access method -> Make RAM allocatable using heap_caps_malloc.

Lowering the clock speed

Finally, the ESP32 defaults to 160MHz but let’s set it to 80MHz for now and see how far we can get on the slowest clock speed. We’d like to be able to run on battery power and lowering the frequency will help to save battery life. We can change it by going to Component config -> ESP32-specific -> CPU frequency -> 80MHz.

If we select Save a file called sdkconfig will be saved to the root of the project directory. We could check that file into git but it has a lot of parameters in it that we really don’t care about. Right now we’re okay with the defaults for most everything except for the above parameters that we just changed.

We can instead create a file called sdkconfig.defaults which will contain only the values we changed above. Everything else will be the defaults. At build time the IDF will read sdkconfig.defaults, override the values that we set, and use defaults for all other parameters.

sdkconfig.defaults looks like this for now:

| |

In total, the initial structure of our game will look like this:

| |

Building and Flashing

The actual process of building and flashing the image is simple enough.

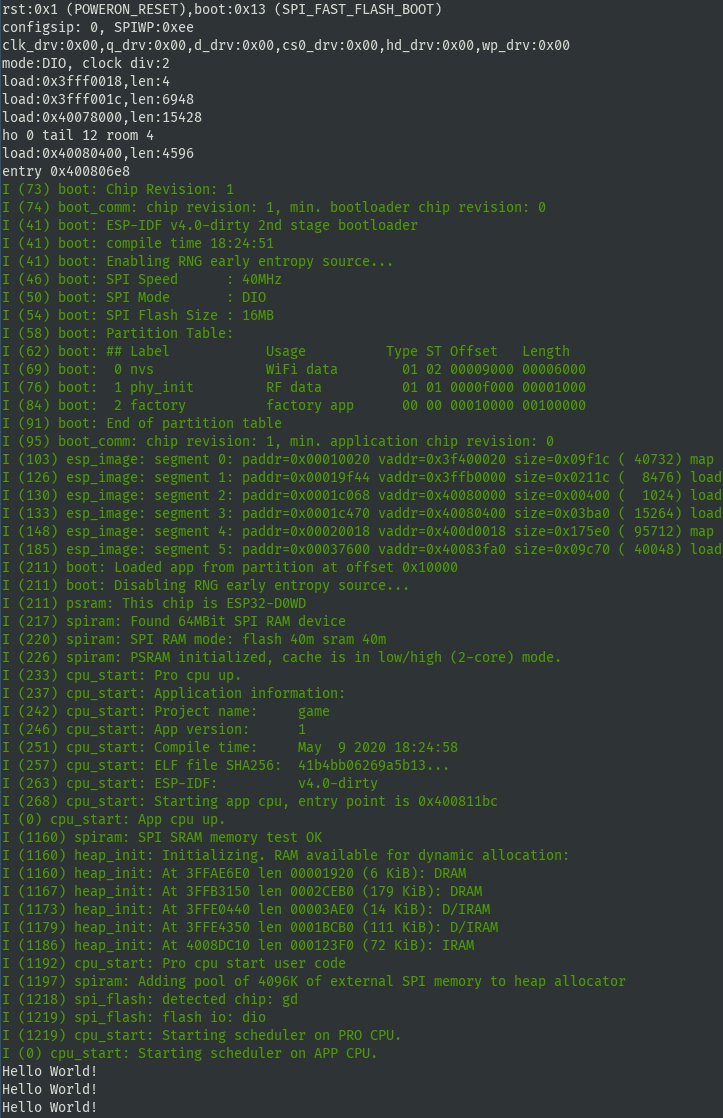

We run make to actually compile (add -j4 or -j8 for a parallel build), make flash to flash the image to the ODROID-GO, and make monitor to view the output of the printf statements.

| |

We could also do them all in one go:

| |

Demo

The result of all of this is not very exciting but it sets us up for the rest of the project.

Source Code

You can find all of the source code here.

Further Reading

Last Edited: Dec 20, 2022